In the fourth episode, the attack on Benghazi is detailed, from the immediate event coverage and later House Select Committee investigation.

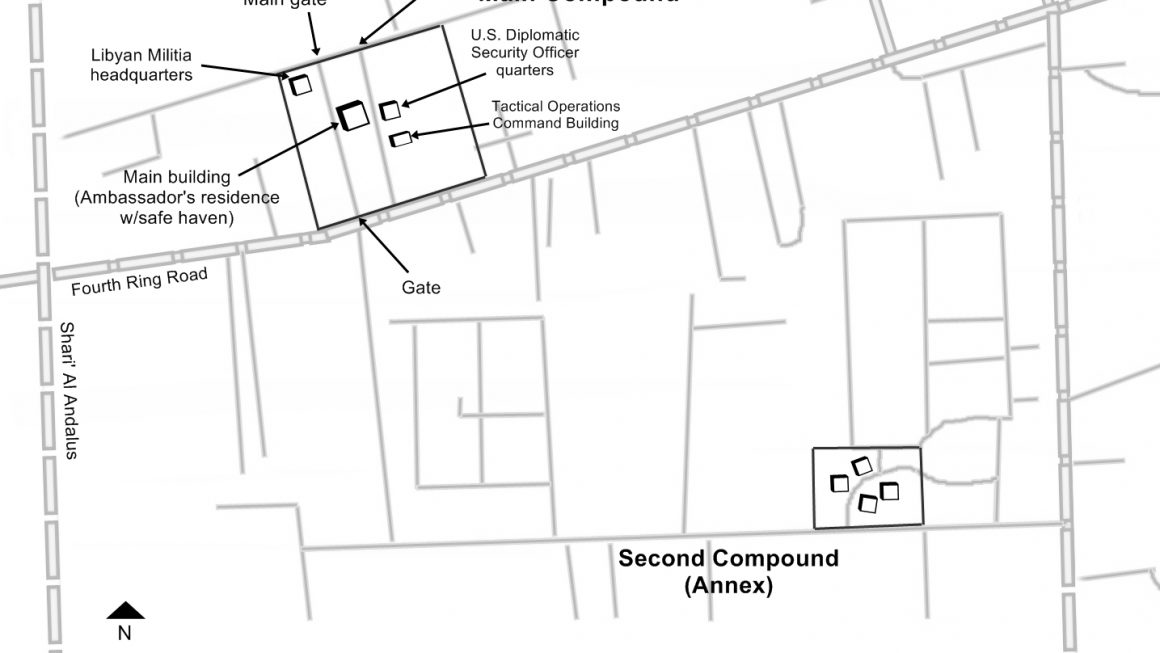

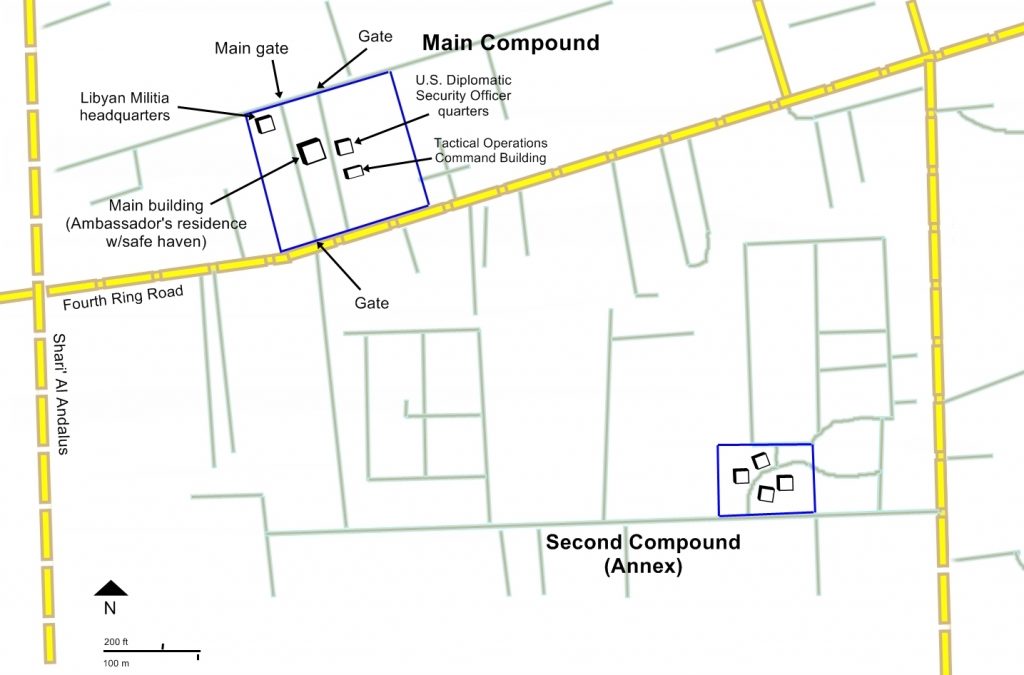

On the evening of September 11, armed militants broke into the main compound of the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya, where there were seven Americans personnel that evening (“Final Report,” 2016). Two were Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and Information Management Officer Sean Smith. The other five were Diplomatic Security Agents. The militants set a “diesel fuel” fire to the building, as Stevens and Smith had followed the Emergency Action Plan, to shelter in a fortified area of the villa as Agents called for security support (“Final Report,” 2016; Ryan, 2012).

One early assumption behind the motives of militants breaking into the compound was the “amateur anti-Muslim” video from the United States, which was translated into Arabic, and caused demonstrators in Cairo, Egypt, and other countries to protest the film (Beauchamp, 2015). Later however, this was denounced, as there was no planned protests (“Final Report,” 2016). However, despite the mission requesting police patrols around the compound, it was not completed and in fact, a police vehicle left as attackers advanced to the compound (“Final Report,” 2016).

As the fire spreads, the Agent with Stevens and Smith attempts to lead them “into the bathroom of the safe haven,” but once there he realizes they did not follow him (“Final Report,” 2016). The Agent escapes the smoke through a bedroom window, and tries to recover Stevens and Smith. Later in the evening, Smith’s body is recovered by Stevens’ is not. A small U.S. and Libyan security team arrives, and after looking for Stevens, they go to the second compound, which goes shortly under attack. There, Navy SEALs turned Central Intelligence Agency contractors, Tyrone Woods and Glen Doherty, are killed. Later, all the Americans leave after the firefights on two flights from Benghazi. Stevens’ body leaves with them, returned at the airport from a hospital where he was taken by Libyans (Ryan, 2012).

Early on, both journalists and politicians linked the Cairo and other Muslim world protests to the Benghazi attack. A few days later, government officials in Libya say the attack was planned (Ryan, 2012). According to the House Select Committee, only later it would become evident that the attackers came from a mix of terrorist organizations, including “Benghazi-based Ansar al-Sharia” (“Final Report,” 2016).

After the attack became publicized, there was outrage, led especially by Republican government officials, over a lack of security on the compound. However, as one agent present in Benghazi testified, there were roadblocks and “gun trucks” surrounding the compound, prohibiting traffic or any “reaction forces” (“Final Report,” 2016). In the next episode, the question of whether it was it an issue of personnel management or of “security spaces” in the compound will be examined, through the lens of Benghazi as a not permanent diplomatic post and in the context of territorial security measures possible in Libya, as well as the political reactions driving these questions (Mamadouh, 2015).

Beauchamp, Zack. “Everything You Need to Know About Benghazi.” Vox, Vox Media, 22 Oct. 2015, www.vox.com/2018/11/20/17996104/benghazi-attack-clinton-obama. Accessed 27 Apr. 2019.

“Remarks by the President of the United States on the Deaths of the U.S. Embassy Staff in Libya.” Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, 12 Sept. 2012, obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/09/12/remarks-president-deaths-us-embassy-staff-libya. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Beauchamp, Zack. “What’s the Precise Timeline of the Events of the Night of the Attack?” Vox, Vox Media, 22 Oct. 2015, www.vox.com/2018/11/20/17996144/whats-the-precise-timeline-of-the-events-of-the-night-of-the-attack. Accessed 12 Apr. 2019.

“Final Report of the Select Committee on the Events Surrounding the 2012 Terrorist Attack on Benghazi.” United States House Select Committee on Benghazi, 7 Dec. 2016, www.congress.gov/114/crpt/hrpt848/CRPT-114hrpt848.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr. 2019.

Mamadouh, Virginie, et al. “Toward an Urban Geography of Diplomacy: Lessons from The Hague.” Professional Geographer, vol. 67, no. 4, Nov. 2015, pp. 564–574. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/00330124.2014.987194.

“Remarks by the President of the United States on the Deaths of the U.S. Embassy Staff in Libya.” Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, 12 Sept. 2012, obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/09/12/remarks-president-deaths-us-embassy-staff-libya. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Ryan, Erica. “Chronology: The Benghazi Attack and the Fallout,” National Public Radio. 19 Dec. 2012, www.npr.org/2012/11/30/166243318/chronology-the-benghazi-attack-and-the-fallout.

“U.S. Mission and Annex Map for 2012 Benghazi Attack.” Wikimedia, Wikimedia Commons, 21 Aug. 2013, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:U.S._mission_and_annex_map_for_2012_Benghazi_attack.jpg. Accessed 10 Apr. 2019.