In the second episode of ‘Unraveling Benghazi’, explore Libya under Muammar Gaddafi, religious radicalism in Libya, and the history of American-Libyan relations.

Libya is a state that has experienced several regime changes, under colonization, dictatorship and monarchy. The country, located in North Africa, between Tunisia, Algeria, Niger, Chad, Sudan, and Egypt, has been historically an agricultural and nomadic farming society (“Libya,” 2019). Benghazi, the second largest city in Libya, is on the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, where it has been a critical port from the third century (“Libya,” 2019).

When oil was discovered in Libya in 1959, it provided revenues which the government and ruling monarchy controlled, using the income to create a welfare state but also to concentrate their personal wealth. The country was rapidly transformed from a poor state to a wealthy one. Muammar Gaddafi, the authoritarian ruler of Libya until 2011, led a coup d’etat in 1969, deposing the royals (“Libya,” 2019). Gaddafi was a proponent of Arab nationalism, and he wanted to remove Western influences. This led to political and ideological suppression, including imprisonments and executions. Pan-Arab nationalism also influenced Gaddafi’s idea to annex with other Arab nations, including Egypt, Sudan and Tunisia (Bates, 2011). From the beginning of his dictatorship until his death in 2011, Gaddafi teetered between fiercely negative international condemnation and some grudging support after declaring a decrease in weapons stockpiling.

By 2011 in Benghazi, a group of people began a “hopeful pro-democracy uprising,” which later became the National Transitional Council, echoing protests in Egypt, Tunisia and Yemen around the same time (Kamat, 2011). The rebels’ aim was to secure freedom of expression and other democratic aims, and the “17 February revolution” became an armed revolt across Libya after just four days of protests, after they became violent over Gaddafi forces’ excessive use of force (Kamat). Rebels’ organizing used elements of social media, as Libyan youth used Facebook to call for protests, calling on families of the approximately 1,200 prisoners killed in Abu Salim in 1996 to support a “Day of Rage” (Kamat).

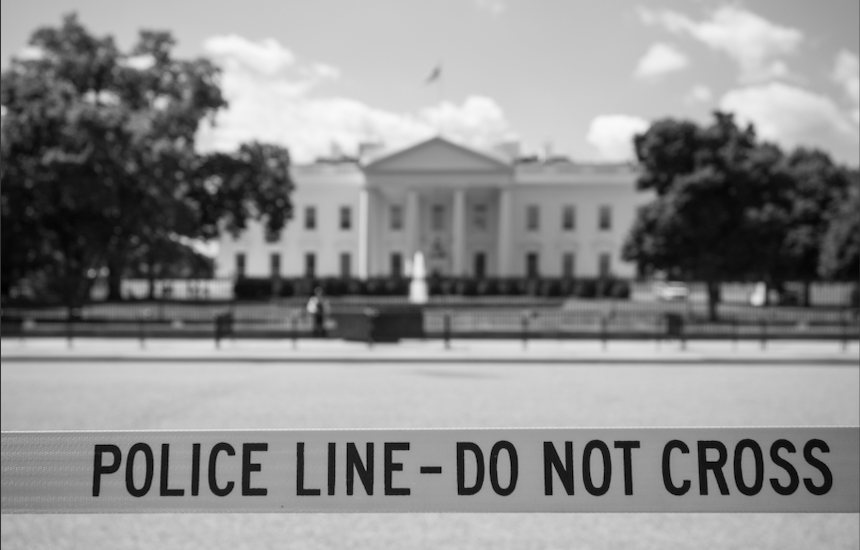

The rebels sought international recognition, with some requesting specifically that there would be no foreign interference, instead asking for “meaningful ways to support their struggle” (Kamat). The United Nations complied, and a no-fly zone was instituted. However, with it, the Security Council also authorized “all necessary measures” to protect civilians (Terry, 2015). This led to North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) use of force by the United Kingdom, the United States and France. By the end of the uprising, NATO flew approximately 9,700 strike ‘sorties.’

In 2012, the U.S. State Department released its annual report on Libya, addressing the end of the civil war and Muammar Gaddafi’s regime.. The report cites violent outbreaks in the country and general government and judiciary instability and the “militia-dominated security environment” in Libya leading up to the 2012 Benghazi attack (Human Rights Report, 2012). Not only were there groups hostile to foreigners after the uprising, but there were many reported instances of discrimination and harassment for minorities, and racial discrimination in Libya, for example kidnappings, torture, imprisonment and other human rights abuses. By 2012 in the post-revolution process, Libya was not yet peacemaking.

“Lust for Libya: How a Nation Was Torn Apart.” Al Jazeera, 18 Oct. 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/the-big-picture/2018/10/lust-libya-181001072826305.html. Accessed 18 Apr. 2019.

Stephen, Chris. “War in Libya – The Guardian Briefing.” The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Ltd., 29 Aug. 2014. www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/29/-sp-briefing-war-in-libya. Accessed 15 Apr. 2019.

Bates, Stephen. “Muammar Gaddafi Timeline.” The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Ltd., 20 Oct. 2011. www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/20/muammar-gaddafi-timeline. Accessed 15 Apr. 2019.

Buru, Mukhtar M. et al. “Libya.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica inc., 26 Apr. 2019. www.britannica.com/place/Libya. Accessed 27 Apr. 2019.

Frayer, Kevin. “Benghazi Rally Protesters.” Associated Press, Encyclopaedia Britannica inc., Mar. 2011. www.britannica.com/place/Libya/History/media/339574/155238. Accessed 27 Apr. 2019.

Kamat, Anjali and Ahmad Shokr. “Libya’s Reformist Revolutionaries.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 46, no. 12, 2011, pp. 13-14. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41151986. Accessed 23 Apr. 2019.

“Libya 2012 Human Rights Report.” U.S. Department of State, 2012, www.state.gov/documents/organization/204585.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr. 2019.

Niedringhaus, Anja. “Libyan Rebel in Ajdābiyā.” Associated Press, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 6 Mar. 2011. www.britannica.com/place/Libya/History/media/339574/155237. Accessed 21 Apr. 2019.

“Port of Benghazi.” World Port Source, www.worldportsource.com/ports/review/LBY_Port_of_Benghazi_666.php. Accessed 25 Apr. 2019.

Terry, Patrick CR. “The Libya Intervention (2011): Neither Lawful, nor Successful.” The Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa, vol. 48, no. 2, 2015, pp. 162–182, www.jstor.org/stable/24585876. Accessed 19 Apr. 2019.